Without getting into details of the Law of Supply and Demand in Economics 101 (something well covered here, as it relates to Google), I think it's worth understanding the impact of abundant supply on the various sectors within the media industry.

The Internet, Schumpeter's latest example of creative destruction, with an unlimited supply of content, broad reach, and (near) perfect performance measurability, has all but crushed the oligopolies that have dominated the media landscape for the past 50+ years. Until the Internet, the primary media outlets were, in order of advertising importance, (a) television, (b) newspapers, (c) radio, (d) billboards, and (e) magazines. And, the way that Madison Avenue determined how to allocate advertising budgets and pricing was (a) sexiness, (b) reach, and (c) measurability. It was simple, television ads are very sexy, can have local or national reach, but have weak measurability. Newspapers present a different reach but are inherently more local. Radio is an auditory experience, therefore more stimulating, but difficult to measure. Billboards can provide local or national audiences and, depending on the target, are more or less measurable. Magazines provide a visual medium with targeted demographics within national distribution, which is great for targeted branding, but difficult to measure.

Then along came the good ol' Internet, which over time continues to provide exponentially better measurability than any of the legacy mediums. And, more importantly, provides better targeting / effectiveness because of the availability (technologically and otherwise) of better consumer data (at a basic level, specific geography, sex, age, and various preferences).

But it's not just the world wide web that's screwed things up! The ad world has been in constant evolution over the past 50 years. The Buggles nailed it in 1981 with their MTV hit, Video Killed the Radio Star. And, now, the digitization of everything has impacted each particular media outlet directly. So, what specifically has happened to the five traditional media outlets over time:

- Television. Ever since the proliferation of cable television, we (viewers, advertiser targets) have faced content overload. In addition to basic broadcast television networks (e.g., ABC, CBS, NBC, CW, Fox, PBS) and local-access television channels, there are now hundreds of other specialized and premium channels, all of who survive largely on advertising revenue (although many also receive subscriber fees from the cable operators for, on average, 5-50 cents per subscriber per month. Without that subscription revenue, many of these cable favorites would not survive. So, not only is the ad revenue threatened by the proliferation of media, but so are other revenue streams threatened by disintermediation. Commonplace living room toys such DVRs threaten ads as does streaming internet video, downloaded video files, Hulu, YouTube, DVDs, AppleTV, Netflix, and on-demand directly from the set-top box.

- Newspapers. The obvious first to bear the brunt of the impact of the Internet, newspapers aren't completely new to competition. At one point, as the only medium really, newspapers held a dominant role in society ever since the movable type at the beginning of the 17th century. However, newspaper magnates were threatened by the proliferation of their own industry, dailies, weeklies, & monthlies, and then magazines and eventually even radio. Over the past century, newspapers have survived the various competitive threats, mainly because of their strong-hold over local markets to deliver local advertising and the ever growing demand for local advertising. However, by the early 1990s the availability of news via 24-hour television channels posed an ongoing challenge to the business model of most newspapers. Paid circulation declined, and advertising revenue (roughly 80% of most newspapers’ income) followed suit. Less than a decade later, the Internet (led by hundreds of news portals and Craigslist), started to take a big bite out of an already weakened industry.

- Radio. The first twenty years of radio thrived in a non-ad supported environment. Many of the first stations that started in the 1920s were owned by manufacturers (for the primary purpose of selling more radios). NBC was started by RCA in 1926. Even once radio stations began relying on advertising revenues, the standard analog television was introduced in the 1940s then color television in the 1960s. Radio barely had time to establish itself as a powerful ad medium before television took the main stage. Interestingly, when radio became more prevalent in the 1930s, many predicted the end of records. Radio was a free medium for the public to hear music for which they would normally pay. Indeed, the music recording industry had a severe drop in profits after the introduction of the radio. For a while, it appeared as though radio was a definite threat to the record industry. Radio ownership grew from 2 out of 5 homes in 1931 to 4 out of 5 homes in 1938. Meanwhile record sales fell from $75 million in 1929 to $26 million in 1938.[*] Sounds familiar, doesn't it? Today, radio (and music sales) are threatened by MP3s (driven by iPods), podcasting, web streaming, satellite radio, and mobile device streaming. Traditional radio stations no longer dominate the car, which was the primary place of use for the past several decades. With mobile phones emerging as media platforms (iPhone) and broadband speeds available over-the-air (3G+), control of audio consumption has been marginalized and user choice is now nearly unlimited.

- Billboards. The out-of-home advertising industry is a little more complicated to synthesize, mainly because it's less "standardized" than the other media. It's also difficult to understand exactly when billboards started, but it certainly happened after lithography was invented, and likely took growth in the mid/late 1800s. Clear Channel is the oldest formal outdoor advertising company in the United States as their roots trace back to Foster & Kleiser, which was formed in 1901. The decrease in printing costs (think PCs and printers) over the past decade has allowed the industry to flourish from initially just outdoor billboards to wall posters, transit busboards, airport ads, shopping mall advertising, subways, taxicabs, and movie theaters. So, not only has the amount of available space (avails) increased dramatically within the industry, now billboard operators are again increasing inventory (and broadening applications) by introducing digital signage (an exponential multiplier effect). Digital signs are now seen, not only on highway billboards, but also in stores, doctors' offices, shopping malls, and gas stations at the pump! Out-of-home is a great source of lead generation for advertisers but this proliferation of choices is quite overwhelming. Advertisers seeking to reach consumers who are "on the go" today not only can choose from the dozens of aforementioned venues, but now can get listed on mobile phones coupled with mapping services or GPS navigation devices (in car or handheld).

- Magazines. Last, but certainly not least, magazines, periodicals, or serials are publications, generally published on a regular schedule, containing a variety of articles, generally financed by advertising, by a purchase price, by subscriptions, or all three. With the exception of, presumably, AARP The Magazine, most magazine titles are facing declining circulation and declining ad pages, which can be a compounding problem because generally circulation drives ad rates. Magazines, by and large, are an ideal advertising medium for contextual branding (golf equipment & services in Golf Magazine or auto-related ads in Car & Driver). And, although many titles have come and gone, the magazine industry traces its roots back to familiar titles such as National Geographic and Good Housekeeping, both of which were launched in the late 1800s. Given such, over the past century, the industry has seen and survived the introduction of radio & television advertising and the evolution of newspapers & billboards. More importantly, the magazine industry itself has created fractionalization. For instance, there are twice as many titles today than a decade ago with two-thirds of the volume. The top 25 titles have been squeezed the most, their unit volume declining by one-half over the decade, only causing more choice (read: difficulty) to the advertiser. This is driven by a major shift in consumer preferences from mass to niche & special-interest titles. Ten years ago, half the volume came from the 25 largest titles; today the proportions have been reversed; almost 75% of volume comes from the several thousand smaller titles. In addition to competition from within the industry, today, magazines are also facing the same threat as the other traditional mediums, the proliferation of web content (and ad inventory) on the Internet. The proliferation & consumer adoption of mobile readers such as Kindles and multimedia devices such as the iPhone presents an entirely new set of parameters for the industry to grapple with.

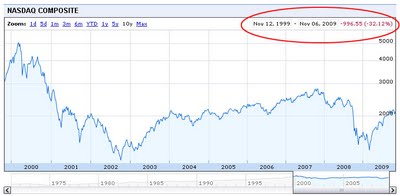

- Internet. Since the days of Netscape & AOL, the Internet has been in constant motion and continuous reinvention. The number of world wide web pages continues to grow at astronomic rates and the availability of content (blogs, books, videos, ezines, photos, etc, etc) does not appear to be slowing any time soon. To address the massive amount of insatiable inventory, hundreds of ad networks have popped up slicing & dicing viewers & advertising opportunities every which way. These ad networks, along with search engines, social networks, and "mega" content portals provide advertising an astounding amount of choice & reach. Mobile content services and online video are both relatively nascent but poised to explode and flood the market with advertising availability. These options, feeding off of tremendous growth, are also fiercely competitive, driving prices down within the Internet sector and also for the other four traditional mediums.

One of the overarching challenges the industry faces is one of resources on Madison Avenue. At the end of the day, enormous budgets are controlled by a relatively small number of actors who seek ease of deployment as much as they do advertising effectiveness. Also, as the Internet continues to commoditize its display ad inventory across increasingly fragmented and nameless ad networks, advertisers will need more, not fewer, places where they can count on a certain quality of content, a quality of audience, and a quality of service. Where will this put the ad rates for so-called long-tail web content? How will those rates compare to broadcast television, magazines, or audio? Will the ad market truly be efficient at pricing? Clearly, we've seen that the stock market isn't capable of it, so why should expect admen to be any more efficient?

The overarching question still holds -- is the ad market a zero sum game? Or, will the demand curve shift to meet this new supply curve? I imagine, like anything, it's likely a combination of the two.